Brain-Gut Dysregulation: When Communication Between Gut and Brain Breaks Down

What Is Brain-Gut Dysregulation?

Brain-gut dysregulation refers to disturbances in the normal two-way communication network (the gut–brain axis) that links our digestive tract and nervous system [1]. Under healthy conditions, the brain and gut continuously send signals to each other via nerves, hormones, and immune molecules to regulate digestion, immunity, and even mood. The gut is sometimes called the “second brain” because it is richly innervated (connected by the vagus nerve and spinal nerves) and packed with neurotransmitters similar to those in the brain. When this bidirectional communication is disrupted—due to stress, infections, inflammation, or imbalances in gut microbes—we observe brain-gut dysregulation. In simple terms, the signals between the brain and gastrointestinal (GI) system fall out of sync, leading to a cascade of physiological changes and symptoms. This dysregulation is now recognized as a key factor in many conditions, from irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) to anxiety and depression [1].

Importantly, disorders characterized by brain-gut dysregulation have no major structural abnormalities; instead, the issues stem from functional and signaling problems. For example, IBS—once thought to be purely a gut motility disorder—is now understood as the most common disorder of gut–brain interaction [3]. In IBS, patients experience recurrent abdominal pain, bowel habit changes, and often anxiety or depression, without obvious tissue damage. Such patterns underscore that a miscommunication between the nervous system and the GI tract can produce very real physical and psychological symptoms, even in the absence of visible disease.

The Brain-Gut Axis: Key Players and Physiology

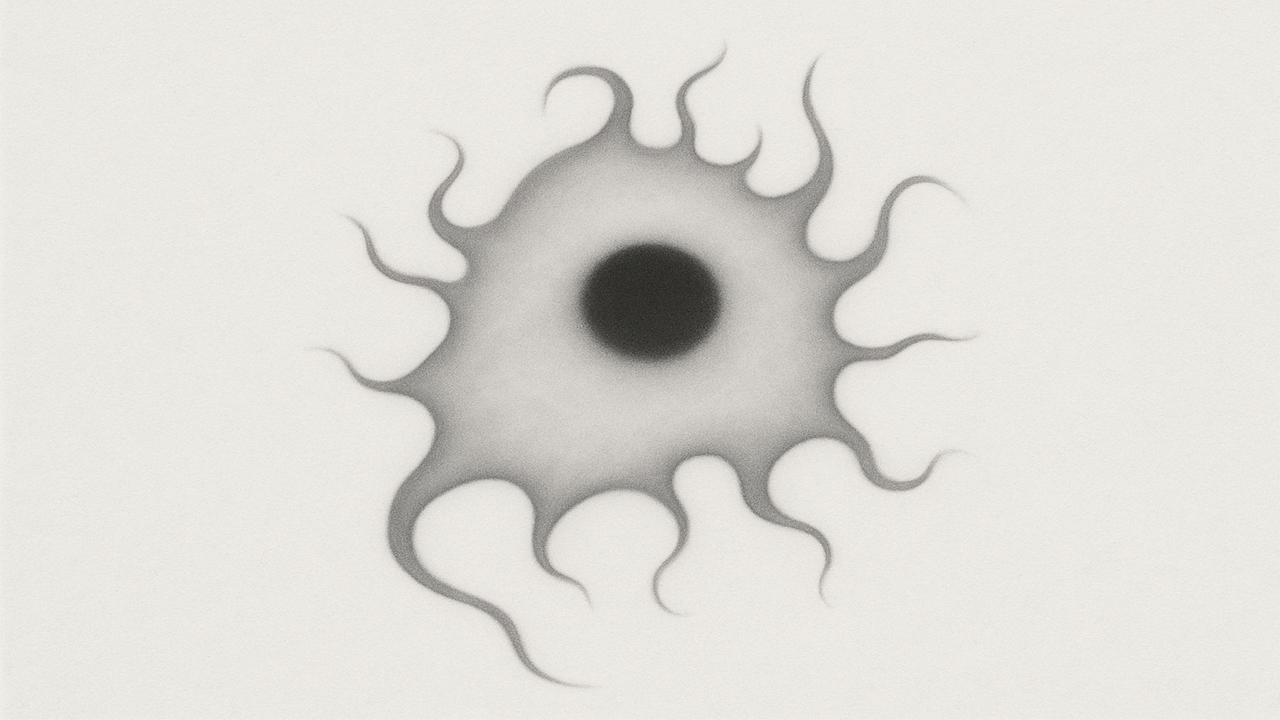

(Figure: Illustration of the brain-gut axis as a bidirectional communication system connecting the gut microbiome with the brain via neural (vagus nerve and spinal pathways), endocrine (HPA axis), and immune signaling. Proper functioning of this network maintains digestive, metabolic, and emotional homeostasis [2].)

To understand dysregulation, we first need to know the brain-gut axis itself. This axis is a complex, integrated system with several key components working together to maintain homeostasis:

Vagus Nerve and Nervous System: The vagus nerve is the main highway of the parasympathetic nervous system connecting the brainstem to the abdominal organs, carrying signals to regulate digestion and from the gut back to the brain [10]. This neural route allows the brain to influence gut movement, secretion, and blood flow, and conversely enables gut stimuli (like distension or irritation) to affect mood and pain perception in the brain.

Neurotransmitters and Hormones: A variety of neurotransmitters are active in the gut-brain axis. Serotonin is a prime example—about 90% of the body’s serotonin is produced in the gut, where it regulates intestinal movements and signals to the brain [9]. Other neurotransmitters like dopamine, glutamate, GABA, and norepinephrine are similarly influenced by gut cells and microbes, shaping both GI function and emotional state. The hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis is the hormonal arm of this system: stress triggers CRH release, leading to cortisol, which changes gut motility, permeability, and immune activity [4].

Immune Signaling: The gut houses a large part of the body’s immune system [5]. Immune cells in the GI lining constantly sample gut contents and can release cytokines that act on the vagus nerve or circulate to the brain. Overactive immune responses in the gut (due to infection or dysbiosis) can create distress signals that drive systemic inflammation and feed back into the brain.

Gut Microbiota: Trillions of microorganisms (bacteria, fungi, etc.) inhabit our intestines, fermenting dietary fibers to produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and other metabolites that influence neurotransmitter systems [6]. A balanced microbiota helps maintain gut barrier integrity and normal emotional function, whereas dysbiosis can disrupt gut-brain communication, fueling both GI and psychological issues.

When these components work properly, there’s a healthy flow of information. But under chronic stress, infection, or dietary imbalances, they can spiral into dysregulation, with the gut sending alarm signals to the brain and the brain returning stress or inflammatory impulses to the gut.

How Does Brain-Gut Dysregulation Occur?

Brain-gut dysregulation arises when one or more components of the axis go awry, leading to a vicious cycle of maladaptive signaling. Key mechanisms include:

Altered Neural Signaling: Stress or trauma can blunt vagus nerve tone, reducing parasympathetic calming. Meanwhile, the gut’s pain-sensing nerves might become hypersensitive (visceral hypersensitivity) [7]. Dysregulated signals mean the brain can misinterpret gut stimuli, causing pain or nausea, and the gut can overreact to brain directives, producing spasms or diarrhea.

HPA Axis Activation and Stress Hormones: Chronic psychological stress can elevate cortisol, weakening the gut barrier and allowing bacterial toxins into the bloodstream [8]. These toxins provoke inflammatory signals that reach the brain, leading to neuroinflammation and altered neurotransmitter systems, thus linking emotional stress to gut dysfunction.

Immune Activation and Inflammation: In a dysregulated gut-brain axis, the immune system leans toward a pro-inflammatory state. Higher levels of cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, etc.) are common in disorders like IBS, and these molecules can affect both gut motility and brain mood centers [9].

Gut Microbiome Dysbiosis: Changes in gut flora—reductions in beneficial Bifidobacteria or Lactobacilli, or overgrowths of Proteobacteria—can upset GI function and produce toxins or shortfalls in helpful metabolites [3]. Dysbiosis often perpetuates inflammation and abnormal nerve firing, further derailing gut-brain communication.

Put together, these factors form a self-reinforcing network. For instance, a gut infection might reduce microbiome diversity, leading to subtle inflammation and nerve hypersensitivity. Pain from normal digestion increases stress levels, boosting cortisol and harming the gut barrier. Microbial imbalance worsens. The outcome is persistent brain-gut dysregulation.

Evidence from Research: Human and Animal Studies

Researchers have pieced together the brain-gut puzzle from both clinical and experimental angles:

Germ-Free Mice: Mice raised without any gut microbes have an exaggerated stress response, releasing higher stress hormones when challenged [7]. Introducing beneficial bacteria like Bifidobacterium infantis normalizes this reaction, showing gut microbes help calibrate the HPA axis.

FMT and Behavior: In a striking experiment, fecal microbiota transplants (FMT) from depressed humans into rats induced depression-like behaviors in the rats [8]. They also displayed inflammation and metabolic changes similar to human depression. Similarly, FMT from IBS patients can transfer IBS-like symptoms to rodents, underscoring microbes’ causal role in gut-brain disorders.

Clinical Observations: Many patients with IBS or mood disorders show biomarker patterns pointing to gut-brain issues [9]. For example, depressed individuals often have distinct gut microbiome profiles, fewer beneficial bacteria, and elevated inflammatory markers. In IBS, imaging shows amplified pain-processing in the brain.

Potential Biomarkers: Studies highlight gut metabolite analysis (like SCFAs) or immune markers (like calprotectin or TNF-α) as possible indicators of brain-gut axis dysfunction [4]. While none are definitive alone, combined panels could one day make diagnosing gut-brain dysregulation more objective.

Overall, animal work and human clinical data converge to confirm that the brain and gut profoundly shape each other’s functioning. Dysbiosis or stress in the gut can spark emotional or cognitive issues, just as emotional turmoil can scramble digestive processes.

Disorders Linked to Brain-Gut Dysregulation

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

IBS is a quintessential brain-gut dysregulation disorder [3]. Defined by chronic abdominal pain and altered bowel habits (diarrhea, constipation, or both) without structural disease, IBS is now viewed as a communication breakdown between gut and brain. Stress often exacerbates IBS flare-ups, and many IBS patients develop anxiety or depression. They also can exhibit a distinct microbial profile—less beneficial species and subtle inflammation in the colon. Therapies aimed at rebalancing the gut flora (like probiotics or low-FODMAP diets) alongside stress management have shown promise in easing IBS symptoms.

Anxiety and Depression

Though traditionally considered purely mental, anxiety and depression frequently involve GI issues and microbiome shifts [5]. Chronic stress or negative moods disturb gut flora and can raise gut permeability (“leaky gut”), which triggers systemic inflammation and modifies neurotransmitters. Conversely, a dysregulated gut can send harmful signals that worsen mood or anxiety states. Studies reveal that certain probiotic strains—sometimes dubbed “psychobiotics”—may mitigate mild anxiety or depressive symptoms, highlighting the bidirectional interplay between gut and brain.

Diagnostic Insights and Biomarkers

Diagnosing gut-brain dysfunction is tricky because no structural damage is visible. Most clinicians rely on symptom-based criteria (like Rome IV for IBS) and ruling out organic disease. However, researchers are developing biological markers:

Microbial and Metabolite Profiles: IBS patients can show specific patterns of short-chain fatty acids or distinct bacterial signatures [9].

Inflammatory Markers: Low-grade elevated cytokines, or slight increases in fecal calprotectin, may indicate subclinical gut inflammation [4].

Stress Hormones and Vagal Indicators: Altered cortisol responses or low heart rate variability can reflect a dysregulated HPA axis and autonomic imbalance [1].

Such biomarker panels, combined with thorough history, could eventually provide more precise diagnoses of brain-gut dysregulation.

Therapeutic Approaches Targeting the Gut-Brain Axis

Lifestyle and Dietary Interventions

Because stress is a central trigger, managing it is foundational. Practices like meditation, yoga, or simple relaxation can lower HPA axis hyperactivity and help restore normal gut function. Adequate sleep, regular exercise, and targeted diets also matter. One widely used approach in IBS is the low-FODMAP diet [3], reducing gas-producing carbohydrates to relieve discomfort and possibly alter the microbiome.

Probiotics and Psychobiotics

Certain strains of Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus have been linked to improved IBS symptoms and mood regulation [8]. One mouse study showed Lactobacillus casei administration reversed depression-like behavior after microbiome disruption. Such “psychobiotics” may work by producing neurotransmitter precursors or by calming the immune response. Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) is more extreme, with success in infections like C. difficile and exploratory benefits in IBS or autism [2].

Targeting the Nervous System

Central Acting Medications: Low-dose antidepressants modulate GI pain and motility (TCAs for IBS-D, SSRIs for IBS-C) [6].

Gut-Focused Psychotherapy: Cognitive-behavioral therapy or gut-directed hypnotherapy helps reframe catastrophic thoughts and reduce maladaptive stress responses [3].

Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS): Preliminary studies show VNS can relieve IBS pain and improve bowel habits by boosting parasympathetic (rest-and-digest) signaling [10]. Non-invasive VNS at the ear has potential to reduce gut inflammation and stress reactivity simultaneously.

Microbiome-Targeted Therapies

Prebiotics: Certain fibers foster beneficial bacteria, potentially lowering anxiety or depressive tendencies [5].

Non-Absorbable Antibiotics: Rifaximin helps some IBS-D patients by knocking down harmful bacterial overgrowth [6].

Postbiotics and Metabolites: Scientists are testing supplements of beneficial SCFAs (like butyrate) or tryptophan derivatives to support the gut barrier and possibly improve mood or IBS symptoms [4].

Conclusion

Brain-gut dysregulation is a paradigm shift in how we view chronic GI and mood disorders. A miscommunication in this axis can manifest as abdominal pain, bloating, and altered bowel habits and anxiety, depression, or cognitive issues—often all in the same person. The physiology involves an orchestra of nerves (especially the vagus), hormones (like cortisol and serotonin), immune cells, and trillions of gut microbes working in concert. Once part of that system falls out of tune, the entire symphony can suffer.

Fortunately, addressing brain-gut dysregulation opens up many treatment avenues. Combining diet, stress management, and potentially probiotics or neuromodulation can help reset that lost harmony. Whether it’s IBS or mood disturbances, focusing on both the gut and the mind is key to lasting improvement. Going forward, personalized approaches—where a patient’s microbiome, stress profile, and immune markers guide therapy—may become the norm. By supporting and nourishing this vital axis, we not only ease physical distress but also bolster emotional resilience, illustrating that the gut and brain truly are two sides of the same coin.

References

Sudo, N., Chida, Y., Aiba, Y., Sonoda, J., Oyama, N., Yu, X. N., … Koga, Y. (2004). Postnatal microbial colonization programs the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal system for stress response in mice. Journal of Physiology, 558(1), 263–275.

Zheng, P., Zeng, B., Zhou, C., Liu, M., Fang, Z., Xu, X., … Xie, P. (2016). Gut microbiome remodeling induces depressive-like behaviors through a pathway mediated by the host’s metabolism. Molecular Psychiatry, 21(6), 786–796.

Camilleri, M. (2021). Review article: biomarkers and personalised therapy in IBS. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 53(6), 654–664.

Chey, W. D., Kurlander, J., & Eswaran, S. (2015). Irritable bowel syndrome: a clinical review. JAMA, 313(9), 949–958.

Cryan, J. F., & Dinan, T. G. (2012). Mind-altering microorganisms: the impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 13(10), 701–712.

Mayer, E. A., Tillisch, K., & Gupta, A. (2015). Gut/Brain axis and the microbiota. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 125(3), 926–938.

Distrutti, E., et al. (2016). Gut microbiota role in irritable bowel syndrome: new therapeutic strategies. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 22(7), 2219–2241.

Breit, S., Kupferberg, A., Rogler, G., & Hasler, G. (2018). Vagus nerve as modulator of the brain–gut axis in psychiatric and inflammatory disorders. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 44.